Frank Lenz: The Lost Cyclist

This article first appeared in the Oct./Nov. 2022 issue of Adventure Cyclist magazine.

Pittsburgh, July 1894. Anna Lenz was the first to sense that something had gone terribly wrong. She had never wanted Frank, her only child, to embark on a round-the-world journey by bicycle in the first place — no matter how much fame or glory that feat might bring him. She feared for his life. She knew how reckless and stubborn he could be in the face of danger, whether introduced by nature or ill will.

Born in Pittsburgh to poor German immigrants shortly after the close of the Civil War, young Frank Lenz grew up with his doting mother and tyrannical stepfather William. The bright and energetic lad was of slight stature, with sandy blond hair and piercing blue eyes. He came of age in the 1880s, when the high wheel bicycle was king of the (unpaved) road, and a familiar — if not always welcome — sight in the Smoky City (so named on account of its bustling industries).

After acquiring accounting skills, including impeccable penmanship, Lenz landed a job at a brass manufacturer and saved up enough money to buy a Columbia roadster with a 56-inch wheel. He joined the Allegheny Cyclers to enjoy all the benefits of the clubhouse. In June 1887, he made his first century ride to Newcastle and back, returning home at midnight. Two months later, he went on his first long-distance tour, to New York City and back.

That fall, Lenz began to dabble in racing on the track and road. His competitive career would culminate a year later, when he narrowly lost a grueling 100-mile road race from Erie to Buffalo. Although he now enjoyed a national reputation, Lenz realized that at five feet, seven inches, he would always be at a disadvantage when competing against long-legged champions mounted on wheels five feet in diameter. He decided to focus instead on combining two passions: cycle touring and photography.

That was no easy task prior to the introduction of the compact Kodak film camera, underscored by a local paper. “Lenz created quite a sensation last Sunday, when he appeared out Forbes Street with a big camera and tripod strapped to his back. The outfit makes a considerable load, but Lenz thinks he is equal to the task.”

In the summer of 1889, Lenz made another trip to New York City and back — this time toting his Blair camera. According to a local paper, in three weeks he took about 150 glass plate exposures of “street scenes, public buildings, bridges, canal streams — anything that looked at all inviting.” After every dozen photos, Lenz mailed the exposed plates home and reloaded his holder with a dozen more fresh plates. Of course, Lenz created a spectacle in his own right, and the locals “mistook him for a peddler, drummer, and quack doctor.”

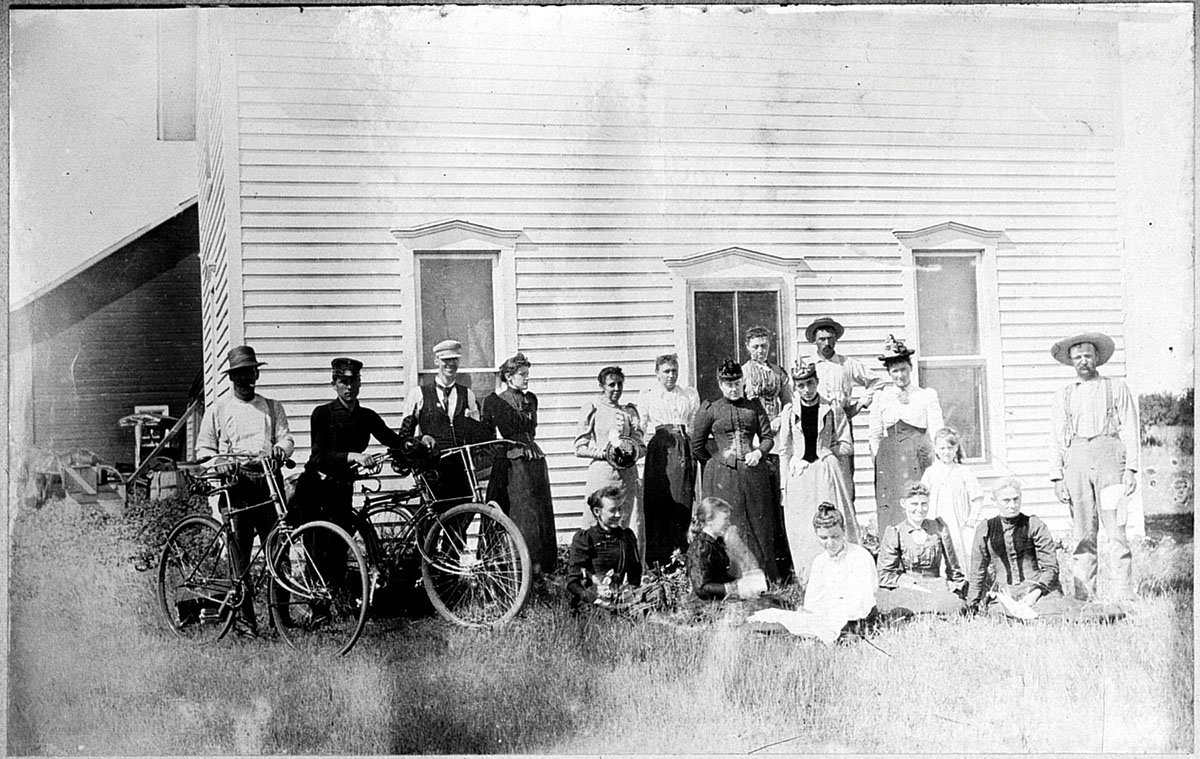

Lenz soon found an ideal riding partner and soul mate in Charlie Petticord. Tall and thin, he had the stamina to keep up with Lenz and he didn’t mind stopping frequently for photo ops. In the summer of 1890, the pair set out from Pittsburgh to Saint Louis, along the famous National Road. The following August, they embarked on an even longer trip to New Orleans. The League of American Wheelmen, the national organization to which they belonged, took note of their feats.

As the year 1892 dawned, Lenz sensed that he had come to a crossroad in life. He was 25 years old, an age when most of his friends had already given up cycling, gotten married, and settled down. His mother and his seamstress girlfriend, Annie R. Leech, wanted him to do just that. But Lenz longed to make one last grand cycling adventure with Charlie.

Lenz had long admired Thomas Stevens, an Englishman who had made a celebrated world tour on his ordinary in the mid-1880s, devouring Stevens’s monthly travel logs published in Outing magazine. He had also heard of Allen and Sachtleben, two Americans who had left London in the fall of 1890 on safeties and were now reported to have reached Asia. Lenz was confident that he and Charlie could outdo the derring-do of both parties.

But Lenz also realized that if he wanted sponsorship, he would have to switch his allegiance to the new safety. He, like most experienced riders, had initially dismissed the diminutive upstart as too low, too slow, and too cumbersome. But now it was the quaint ordinary that had become an object of ridicule.

Lenz secured the support of J. H. Worman, the editor of Outing, and of A. H. Overman, the maker of Victor Cycles, for a world tour with bicycle and camera. Lenz stressed that he would not seek to break any speed records. Rather, his mission would serve to educate the public — largely new to the sport — about the joys and benefits of cycling.

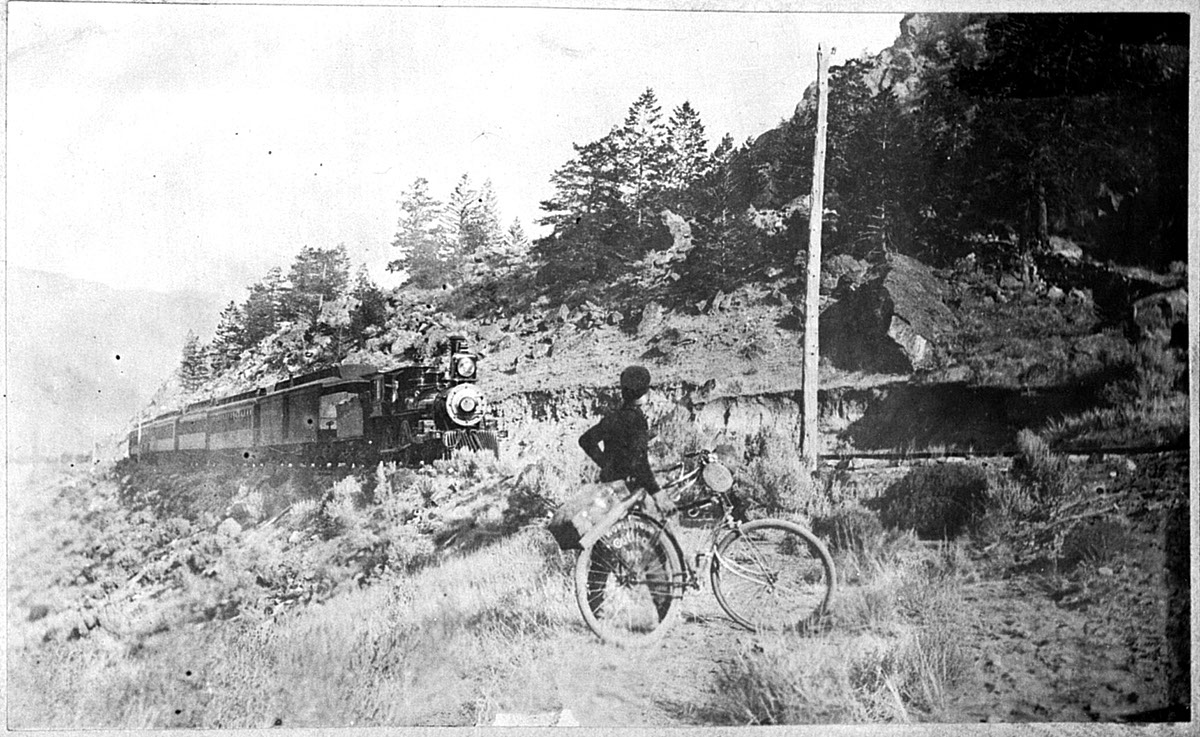

Even when Petticord begged off at the last minute, citing a job promotion, Lenz was determined to go through with his plan. To add some novelty to his tour, Lenz boldly chose to travel on a Victor equipped with newly introduced pneumatic tires. But rather than use the latest compact Kodak film camera, as Allen and Sachtleben were doing, he insisted on bringing his usual gear to get optimal photographs.

On May 15, 1892, Lenz made his unofficial departure from Pittsburgh. He estimated his total load at 240 pounds, comprised of his camera at 15, other gear (which presumably included his revolver) at 25, his bicycle at 57, and himself at 145. He then rode to New York City, where Outing was based. The magazine arranged for a grand send-off down Broadway, and thousands on the street and leaning from windows cheered on the aspiring “globe girdler.”

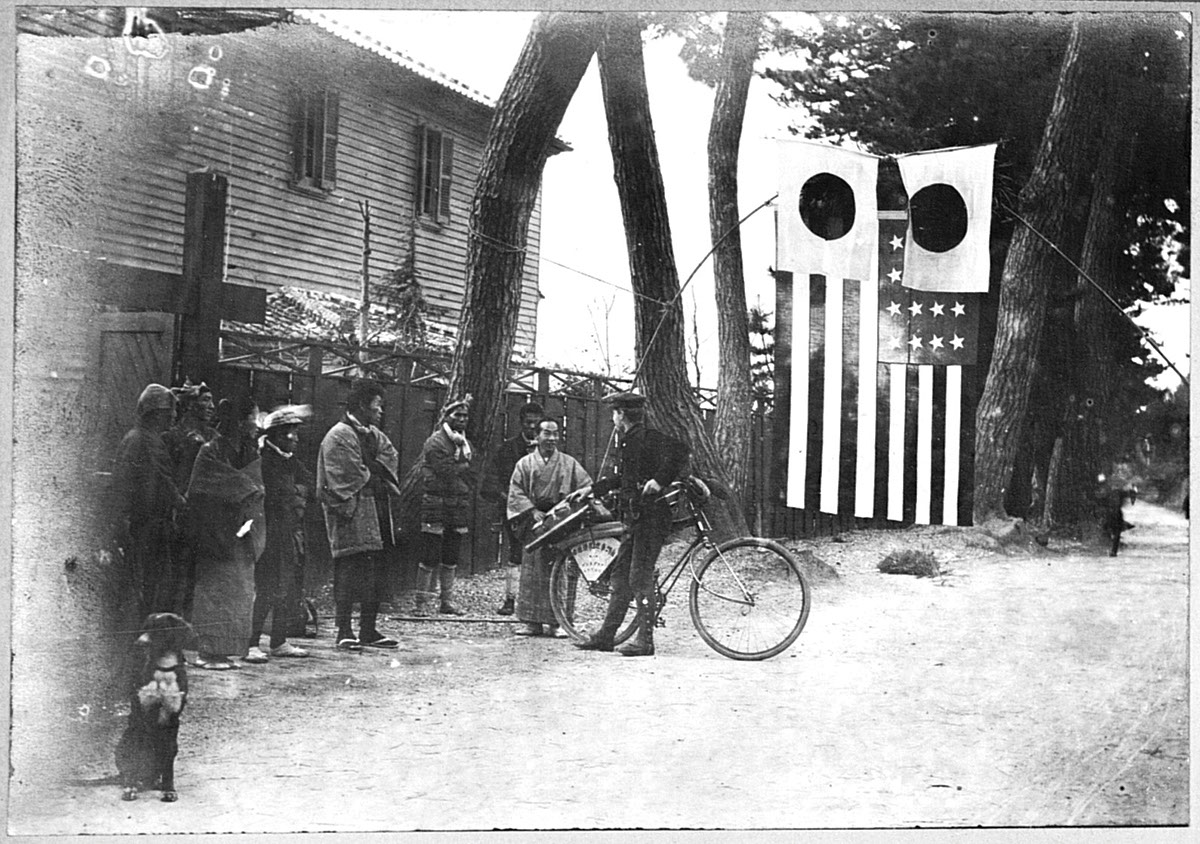

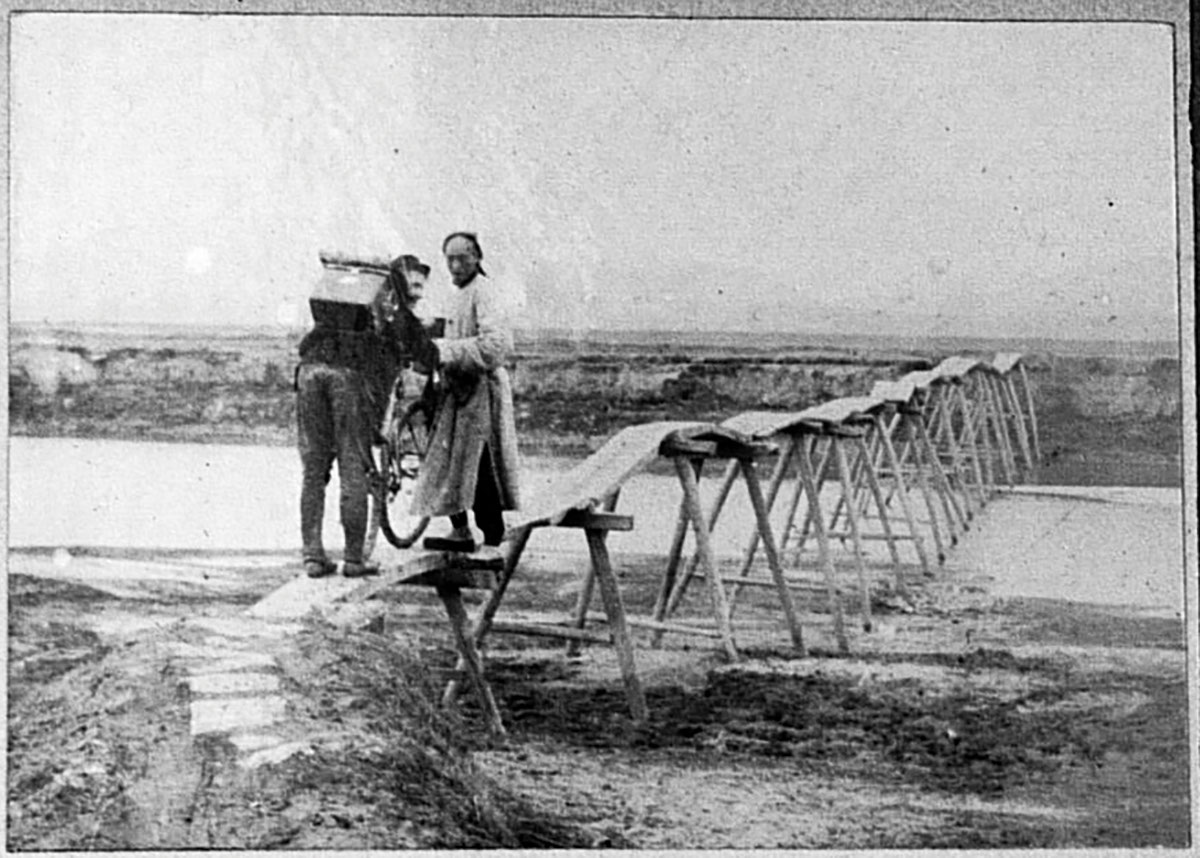

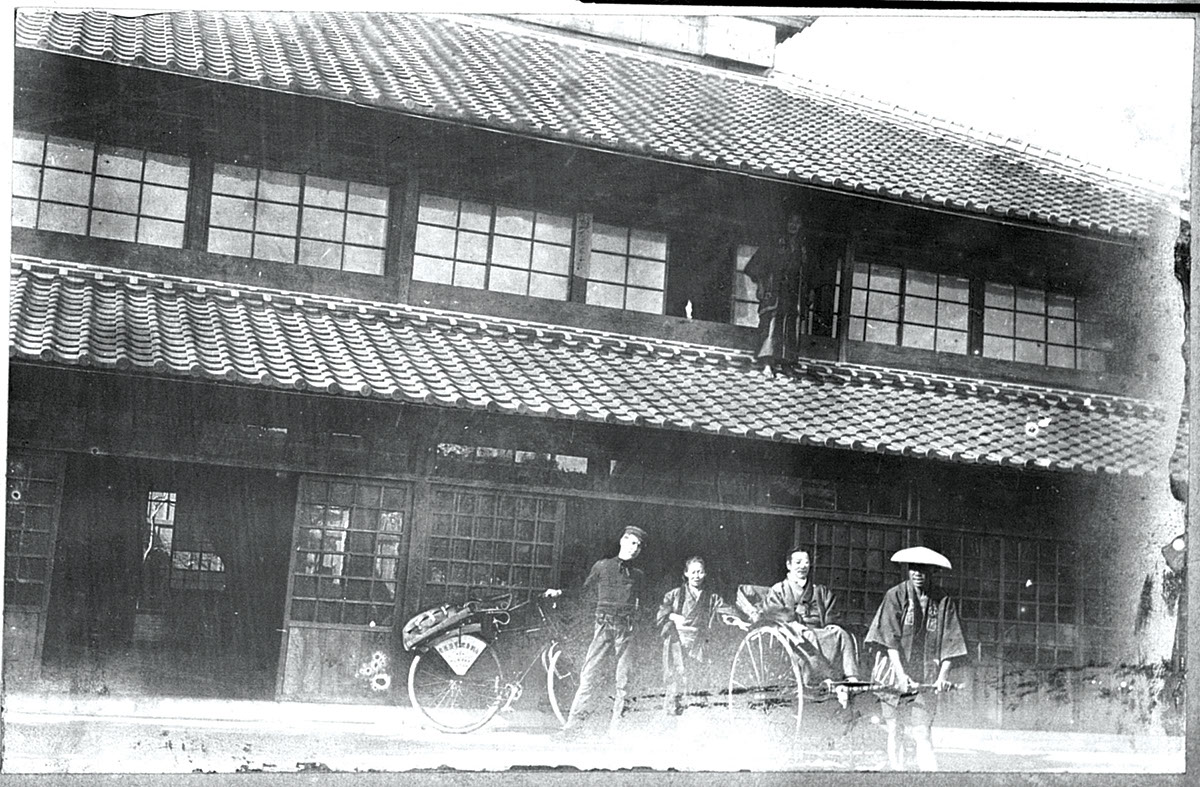

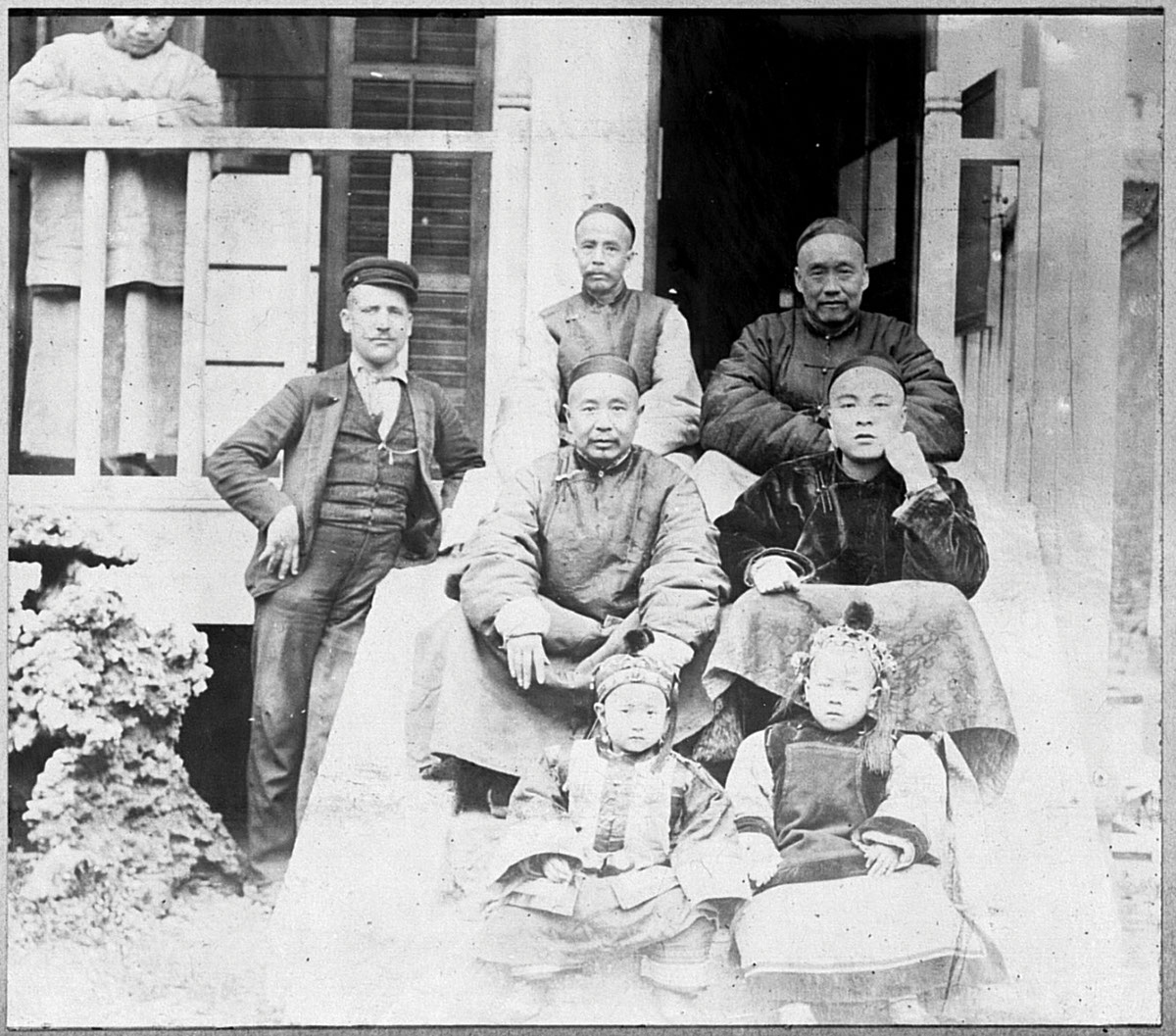

The following two years were crammed full of adventures, most of them chronicled in Outing. He crossed the U.S. from east to west, highlighted by a visit to Yellowstone. He then spent a month cycling through scenic Japan, his first exposure to a foreign culture. Then came forbidding China, what he deemed the most challenging part of his journey. After braving the monsoons of Burma, he crossed friendly India and arid Belluchistan (Pakistan) before finally reaching exotic Persia (Iran).

In late April 1894, Lenz arrived in Tabriz, where he was received by the crown prince at his palace. The cyclist left that Persian city after a week, by all accounts healthy in body and spirit, and confident that the worst travails were behind him. Lenz’s plan was to make the 1,100-mile trek to Constantinople (Istanbul) via Erzurum, Turkey, before crossing Europe for the final stretch, including a visit with relatives in Germany. He longed to be home as soon as possible, he wrote Charlie.

Lenz was expected to arrive in Erzurum in about 10 days, at which point he planned to send Outing another packet of reports. But June came and went, and the magazine still had not received anything from Lenz since Tabriz. Then in July came an ominous cable from Thomas Cook & Sons notifying Mrs. Lenz that her son’s trunk and mail were still awaiting pickup in Constantinople.

Anna was terrified. She was keeping a rough track of her son’s progress, not from the Outing magazine series (which lagged about six months behind real time) but from the regular letters that Frank had promised to write her (only about a month behind). She knew that he had made it to Tabriz, even as the public was speculating that Lenz had perished in the sands of present-day Pakistan. But she had not heard anything more from him in two months.

Anna turned to her brother-in-law Fred Lenz, who wrote the Outing editor asking for an update on Lenz’s fate. Worman acknowledged that he too had not heard from Frank since he had reached Tabriz, but he stressed that there was nothing to worry about. After all, Lenz had gone silent a few times before only to reemerge in fine form. He continued to publish Lenz’s accounts without expressing any concern for his well-being.

Privately, however, the editor knew something was wrong. He discretely dashed off letters to the American ministers in Persia and Turkey to inquire whether they had any news of Lenz — knowing that it might take two months for a reply (unless the recipients paid for an expensive cablegram). Lenz’s friends, meanwhile, began to meet regularly to discuss what to do. T. J. Langhans wrote and cabled various missionaries in Persia and Turkey to establish Lenz’s last known whereabouts.

Lenz had evidently disappeared somewhere along the 365-mile stretch between Tabriz and Erzurum, skirting the western border of present-day Armenia. The Persian portion — the first third of that journey — was particularly rugged, filled with narrow mountain passes. Various rivers along the way were at their peak levels that time of year. The locals, especially the nomadic Kurds, were known to rob vulnerable travelers.

The fear that something had happened to Lenz was soon compounded by sensational reports in the western press of Armenian massacres taking place near the Turkish portion of Lenz’s route. Conceivably, Lenz could have been an unintended casualty of that violence, or perhaps he had been intentionally killed simply because he was a westerner. Alternatively, if he was still alive, perhaps he had been temporarily incapacitated, gone into hiding, or kidnapped.

Increasingly desperate, Anna turned to another relative, attorney John J. Purinton of East Liverpool, Ohio. That fall, frustrated by Worman’s lack of action, he wrote the secretary of state to demand an investigation into Lenz’s disappearance. He also alerted the local papers that Lenz was missing, and soon the disturbing news was picked up by papers across the country.

As the weeks went by without news from Lenz or his presumed captors, any hope that he was still alive faded. True, some skeptics suggested that Worman and Lenz were colluding in an elaborate publicity stunt designed to sell more magazines. But Petticord immediately shot down that preposterous notion. “Oh, tut tut nonsense. Frank would never enter into such a scheme. He knows such silence would almost kill his mother. No amount of money could hire him to hide himself.”

Even the idea that Lenz was temporarily waylaid and unable to communicate with the outside world seemed increasingly unlikely. The American missionary W. S. Vanneman in Salmas, Persia, who had seen Lenz a few days after the wheelman had left Tabriz, insisted, “Had he been taken sick in a village, he would have had no difficulty in getting word to someone to come to his help.”

That left only one faint hope that Lenz was still alive: a kidnapping. Worman convinced himself that this was the most likely scenario, and he braced himself for a belated communiqué from Lenz’s captors. Meanwhile, he continued to assure everyone that all would turn out well. He resisted growing calls from Lenz’s friends to send a search party, assuring them that he had already asked the Constantinople office of Thomas Cook & Sons to send native guides to track down Lenz’s last known whereabouts. (As it turned out, the company was unable to secure Turkish permission to send anyone to that troubled region.)

By early 1895, it was clear that the famous wheelman was dead. But where were his remains? They would be needed to give Lenz a proper Christian burial back in Pittsburgh so that his inconsolable mother would have at least some sense of closure. And they would also provide the proof of death necessary for her to collect on the $3,000 life insurance policy that Frank had discretely purchased just before his departure.

Of course, the other agonizing question was this: how did Lenz die? Was it an accidental death, or was he the victim of foul play? If so, the murderer(s) must be identified and prosecuted, and the host country (Persia or Turkey) must be forced to pay an indemnity to Mrs. Lenz.

“There can hardly be any question that [Lenz] perished, in one of two ways,” Vanneman offered, “either he was drowned in crossing a river, or fell a victim to Kurdish violence. Which of these two is the more probable depends upon what point he is known to have reached.” By the missionary’s reckoning, if Lenz had gotten past Karakalissa, Turkey, he must have been killed, since there were no major streams to cross between that point and Erzurum.

A Canadian missionary in Erzurum, William Nesbitt Chambers, whose help had been enlisted as well, wrote that he had heard reliable reports that Lenz reached Diyaden, Turkey, on May 7, 1894. Chambers soon got another report that Lenz spent the night of May 9 in a farmhouse in Chilkani (today Güvence), 50 miles west of Diyaden. Since that town was past Karakalissa, it now seemed clear that Lenz had been killed. Indeed, according to Chambers’s source, the villagers heard rumors to that effect shortly after Lenz’s visit.

Robert W. Graves, the British consul in Erzurum, who was also investigating the Lenz matter, gave this somber conclusion: “Your relative must have been robbed and made away with somewhere in the dangerous district of Bayazid or Alashgerd. It will be difficult now to clear up the mystery of his disappearance.”

Lenz’s last approximate location now seemed reasonably clear, and the next obvious step was to send an investigator to that area to recover Lenz’s remains and identify his murderer(s). Worman, under mounting pressure, announced in January 1895 that he would send Robert Bruce, his former editorial assistant, to Turkey. Bruce had accompanied Lenz halfway across the U.S., so he was well familiar with the victim. Following resolution of the Lenz matter, Bruce planned to symbolically complete Lenz’s journey from Tehran on bicycle, writing his own reports for Outing.

Lenz’s friends, however, having lost all faith in Worman, were planning to send an investigator of their own: the famous cyclist William L. Sachtleben, who had cycled through that very area three years earlier on his own world tour with Thomas Allen, Jr. Not wishing to see two independent investigations, Worman sought out Sachtleben, and after the two agreed to terms, he dismissed Bruce. Now it would fall to Sachtleben to determine Lenz’s fate and to finish his journey for Outing.

Worman, however, continued to stall, perhaps still half hoping that he might finally get a ransom demand. He insisted that it would be pointless for Sachtleben to go to that region until the winter snow had fully melted, though the wheelman was impatient to get started. Meanwhile, a report surfaced in Europe that Lenz had been ambushed in the Deli Baba pass, some 25 miles farther to the west than Chambers had traced him. Sachtleben knew that notorious wild mountain gorge well. “Allen and I were warned not to take this route, but we had no choice. And Lenz’s position would be more dangerous than ours. We could watch all sides, while he could face only one way.”

Finally, in late February, Worman gave Sachtleben the green light to make his way to Constantinople. Three weeks later, after brief stops in Paris and Vienna, Sachtleben finally reached the Turkish capital aboard the celebrated Orient Express. His first order of business was to meet with the American minister to Turkey, Alexander W. Terrell, a career politician from Texas, to secure permission from the Turkish government for passage to Erzurum and points farther east.

Terrell had little sympathy for either Lenz or Sachtleben, both of whom he regarded as foolhardy. He assured Sachtleben that Turkish authorities had already looked into the Lenz matter before giving it up as “unfathomable.” He stressed the horrors of the ongoing Turkish assault on Armenians and the determination of the authorities to bar all foreigners from that region. “No, young man, let me advise you to return the same way you came. Take my advice, use your wheel on the other side of the water in God’s country.”

Sachtleben retorted that he would not be derelict in his duty, nor would he return home a laughingstock. Terrell begrudgingly pledged to do his best to get the travel papers from the Turkish government. But as Sachtleben stormed out of Terrell’s office, Luther Short, the consul general, issued a dire warning: “You’d better be careful, young man, or your bones, too, will find a resting place in some Armenian grave.”

After weeks of frustration, Sachtleben managed to finagle his own papers authorizing travel as far east as Erzurum. He hired a “dragoman,” a Christian Arab named Khadouri, to accompany him and to serve as his interpreter and personal assistant. He was elderly but fit, with a white beard and a turban. But by the time the pair got to Erzurum, it was mid-May 1895 — exactly a year after Lenz was supposed to arrive there. Sachtleben knew well that the lengthy delay may have cost him valuable clues to Lenz’s death.

Sachtleben got a warm reception from Graves and Chambers, who took him in as a houseguest. The 42-year-old missionary had taken a deep interest in the Lenz case ever since Anna Lenz had approached him for help eight months earlier, and he was eager to help the investigator any way he could. Sachtleben knew that Chambers, with his deep knowledge of the local culture and languages after 15 years in Turkey, was an invaluable resource.

But Sachtleben was still about 100 miles west of where Lenz had disappeared, and he would need more papers to get any closer to his target, inducing yet another lull and further correspondence with Terrell. To help bide his time, Sachtleben convinced Chambers to join him in a hike up Mount Ararat in nearby Armenia, a feat that he and Allen had already accomplished four years earlier.

In late May, while still in Erzurum, thanks to Chambers and Graves, Sachtleben was able to secure the services of Khazar Semonian, an Armenian who lived near Chilkani. The “spy” confirmed that Lenz had stayed at a farmer’s house in that village shortly before the locals had heard rumors of the cyclist’s demise. The spy also interviewed residents of Zedikan, 10 miles west of Chilkani, and they did not recall seeing a cyclist pass through town a year earlier, suggesting that Lenz had not reached the Deli Baba pass after all.

Moreover, the spy determined that a few days after Lenz came to Chilkani, local boys had discovered what he believed to be remnants of Lenz’s gear: “a small hand-mirror and a small box broken in pieces, and a lot of shiny paper” in the river Hopuz, about six miles northwest of Chilkani. Indeed, the spy had heard that, around the same time, a naked body matching Lenz’s description washed up in the nearby river Sherian.

The local authorities had the body buried in Kolsh, a Kurdish village on the south side of the Sherian. Hearing rumors that local Kurds possessed pieces of Lenz’s bicycle, the spy posed as a peddler looking to buy scrap metal. He purchased a piece of a bicycle bell from one, and he spotted rubber tubes dangling off a saddle at the home of Moostoe Niseh, though he was unable to purchase the object. The spy immediately fingered Niseh as the likely culprit, describing him as “a notorious robber and murderer.”

By early June, Graves’s sources had confirmed that Niseh was the ringleader who had killed Lenz and had identified five other Kurds as his accomplices. Sachtleben was now convinced that he had all the information he needed to carry out his mission. “I do not merely want to find Lenz’s grave,” he wrote Worman, “I want to see these murderers punished and an indemnity paid.” He asked Terrell to get the Turkish authorities in Constantinople to put pressure on the local vali (governor) to provide him with 10 zapitehs (armed guards on horseback) to assist in the house searches and arrests.

Even as he continued to seek help from Terrell, Sachtleben cabled Mrs. Lenz and urged her to appeal directly to the secretary of state, Walter Q. Gresham, for immediate action. Sachtleben wanted the U.S. Navy to dispatch two man-of-wars (frigates) to the Turkish coast as a show of force and to demand the immediate arrests of the accused Kurds and a $50,000 indemnity for Mrs. Lenz.

Terrell cabled back to say that he was doing everything possible, adding “Haste cannot bring back the dead.” Sachtleben vented to Worman: “Terrell made me wait five weeks at Constantinople and more than seven weeks here [in Erzurum] and then did not help me a bit.” July came and still no word from Terrell, though Sachtleben did receive a letter from Outing with a photo showing Lenz’s “peculiar” teeth, to be used to identify his skeleton.

Then Sachtleben learned that Terrell had turned over the names of the suspected Kurds to the Sublime Porte (the central authority of the Ottoman Empire), a move the wheelman was certain would backfire. He feared that the central authorities would forward the names to the local vali, who in turn would alert the accused and give them time to destroy evidence or simply disappear before the arrival of Sachtleben and his guards.

August came, and Sachtleben still had not secured a commitment from the vali to provide him support to hunt down and arrest the accused. Terrell wrote Sachtleben, “Be still patient for a while, and remember that I have neither an army or a navy to assist you.” The minister added testily: “I have been attempting to learn the fate and who are the murderers of Mr. Lenz long before you came.”

At last, in early September, came good news from Terrell. Shakir Pasha, a Turkish war hero, was about to conduct a tour of eastern Turkey to implement internationally imposed reforms designed to stop the massacres of Armenians and alleviate ethnic tensions. He agreed that Sachtleben and his assistants, including Chambers, could join his entourage, and he would oversee an investigation into the Lenz affair and provide the means to make appropriate arrests.

Sachtleben ultimately determined that Niseh and his men had called on Lenz at the farmer’s house in Chilkani, only to find the exhausted wheelman fast asleep. Lenz allegedly awoke to find the Kurdish chief fingering Lenz’s revolver, whereupon the wheelman snatched the weapon back. This action purportedly humiliated the Kurd in front of his men, and the next morning, they ambushed and killed Lenz just as he left town.

Shakir had Niseh and his men arrested, but they ultimately escaped prison and were never brought to trial. Sachtleben never did find Lenz’s remains, though he did manage to get Mrs. Lenz a small indemnity from the Turkish government, but without any formal admission of responsibility for her son’s death.

In retrospect, it seems a safe conclusion that Lenz was killed by assailants. There also appears to be evidence that he was ambushed outside of Chilkani on the morning of May 10, 1894, presumably by Niseh and his men. But was he actually killed there? Without knowing where his grave is, it is difficult to know for sure. Conceivably, Niseh and his men roughed Lenz up, stole and destroyed some of his gear, but left him alive. That could explain the original reports that Lenz was killed some 25 miles farther along, on the Deli Baba pass, perhaps later that same day or the following day, presumably by other brigands.

We may never know the full story, and Lenz’s demise is likely to remain a mystery. Sadly, his poor mother never got the closure she desperately needed. For decades, until her own death, she reportedly never gave up hope that her wayward son would appear one day at her doorstep, smiling and clutching his bicycle.

Comments

Wow, what a riveting true-crime mystery. Terrible tragedy, but admirable profile of Franz Lenz and outstanding read. Hats off, David Herlihy and Adventure Cyclist!

What a remarkable story! Soon, I will be embarking on a month-long solo journey up the coast of Vietnam and will be no-doubt thinking about this tale often as I make my way.

Lenz and pioneer long-trip bicyclists like him were truly amazing. Imagine pedaling nearly every day on lousy, rutted roads on rudimentary bikes and burdened by bulky items and camera equipment. What courage to do it alone!!

Forgot Password?

Enter your email address and we'll send you an email that will allow you to reset it. If you no longer have access to the email address call our memberships department at (800) 755-2453 or email us at memberships@adventurecycling.org.

Not Registered? Create Account Now.