The Chocolate Connection

A version of this story ran in the August/September 1983 edition of BikeReport. This version appeared in the June 2016 issue of Adventure Cyclist magazine.

Huddled around a café table in the tiny Mexican village of Chocolate (choc-o-la’-tay) and absorbed in the future, we were only vaguely aware of the café’s daily routines. Huge, black iron kettles full of chopped- up pork meat simmered over open fires on the barren dirt yard out front. My husband, Greg, had captured the cooking process, part of the facade of the café, and several locals on film, but otherwise our four cameras sat idle. Preoccupied with a new idea, we forgot to photograph our conversation. But that meeting would have a tremendous and lasting effect on the future of bicycle touring in the U.S.

It All Started with Hemistour

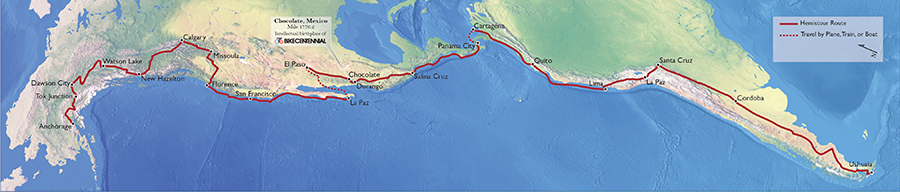

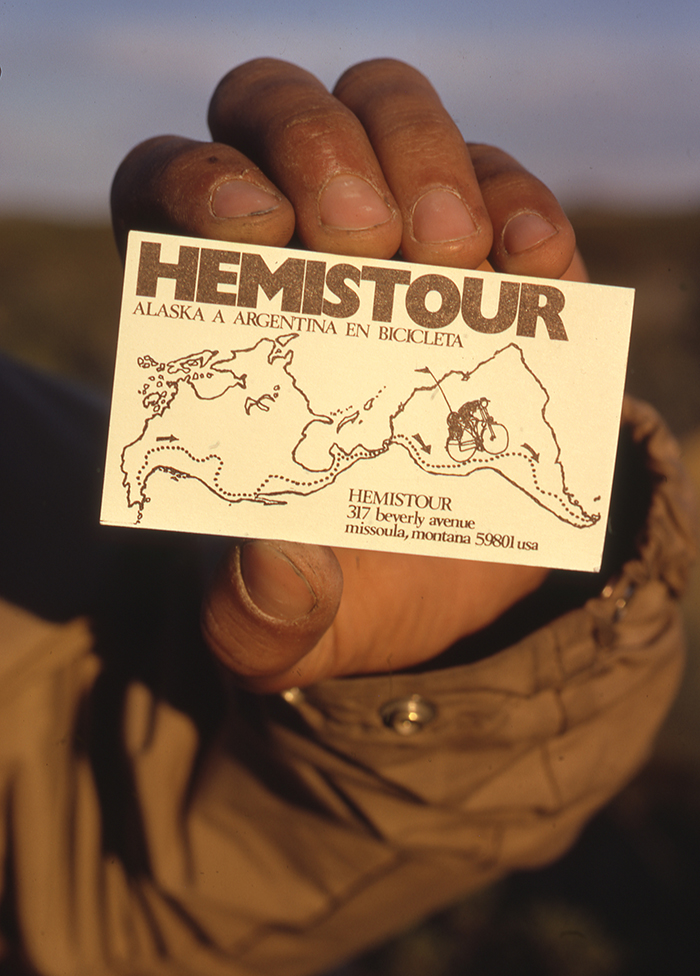

Hemistour was on the road. We had traveled from Anchorage, Alaska, gathering companions here and there and seeking publicity to help bicycle touring grow in America and to promote hosteling. National Geographic magazine had scheduled a Hemistour article for the following month — May 1973 (see story in April 2016 Adventure Cyclist). The support, the recognition, and the publicity we sought through Hemistour — all were in hand. Greg and I would eventually push on to the tip of Argentina to finish the expedition’s goal of riding bicycles from Alaska to Argentina, the length of the Western Hemisphere.

Nearly everyone we met seemed astounded at the notion that bicyclists could actually ride that far. Some even rejected the idea as preposterous. In 1973, extended bicycle touring was a relatively new idea to the American public.

During March in Mexico, the heat had not yet come with full force to the northern desert. The scent of mesquite trees in bloom, new to us, was intoxicating, and the coolness of the season kept the rattlers and scorpions at bay. We knew the heat would come eventually, and the occasional hot day forced rest stops in the shade if we could find any. Infrequent wind gusts whipped dry soil into the air, obscuring our vision. Distant blue mountain ranges patiently slid by as we headed south along relatively quiet roads through the center of mainland Mexico. Time was ours, though we chose not to wear watches. Within the expanse of this new environment, we had plenty to think about, such as the realization that we had left our own borders, and the heart-stirring fact that a Hemistour article would soon be in the hands of 8.5 million National Geographic readers.

Greg, Tom Robson (a Canadian from Waterloo, Ontario), and I had been the last to leave our campsite that morning near an irrigation canal pumping station south of Torreón, Mexico, on April 3, 1973. It seemed the beginning of an ordinary day on the road, but Greg was entertaining an extraordinary idea. By the time we caught up with Dan and Lys Burden, who were waiting for us in Chocolate’s café, we three had already talked about Greg’s basic concept. Then, like another little whirlwind in the desert, the five of us brainstormed it intently around the café table. At Hemistour mile number 6,880, at Chocolate’s café, with pork pots bubbling outside, our contribution to the U.S. Bicentennial summer celebration took shape.

We had found extended bicycle travel very appealing, and the 1976 Bicentennial would be an ideal time to launch a cycle touring event and invite the public along. Greg’s original concept was to meet up with other riders who wanted to join us in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, at a scheduled date and time. Cycling en masse, we would cross the U.S. in a Tour of the Scioto River Valley (TOSRV)-style event with thousands of riders and finish in Philadelphia.

That day we only managed to accomplish 44 miles, but by the time I arrived at our campsite at the edge of a plowed field on the road to Nazas, I had come up with a sweet contribution to the new project: its name, “Bikecentennial.” When I checked my cyclometer to give Greg the total mileage for the day for his journal, I was dumbfounded because the cyclometer read 1776.2 miles. I snapped a couple of photos to document it. Who would believe such a coincidence otherwise? In a flash, the others shouted out “Two Wheels, Two Centuries!” for the “.2” of a mile. Greg wrote the only journal entry that day, “Much talk about BIKECENTENNIAL that June names.”

Public Support

As we continued our adventure through Mexico, the realization that the event was only three years away nagged at us. Three years was not very long to organize something so ambitious, and who was going to organize it while we continued cycling to Argentina?

Nevertheless, we forged ahead and promoted it. To tease the U.S. cycling public’s curiosity, we mailed our first classified ad plus $1 to Bike World magazine on April 16, 1973, to place in the June/July issue: “TOSRV TO HEMISTOUR TO BIKECENTENNIAL.” The August-September issue carried our second classified ad: “TOSRV PLUS HEMISTOUR EQUALS BIKECENTENNIAL,” and Bike World reprinted the text of our first Bikecentennial flier, which we had produced by the end of May in Mexico. By the October-November issue, a third classified ad hinted even more at the event to come: “BONETINGLING, Kaleidoscopic, Multitudinous adventure from brine to brine, backroading it for seventy days — BIKECENTENNIAL 76.”

We sought advice from the people we most respected within the sport, as well as friends and family. After telling them about our ideas, we hoped they would lend enough wisdom to keep us on track. The first 30 fliers describing Bikecentennial went into the mail on May 30, 1973, at a cost of $2.40. By July 13, we had mailed more than 100 “BIKECENTENNIAL 76...TWO WHEELS TWO CENTURIES...” fliers from Mexico to our U.S. advisors. Even more fliers would be mailed from the States during an upcoming break in riding. For the first time, those involved in various aspects of bicycle touring in America would rally around a cause — Bikecentennial. Responses to our flier began to arrive at our Mexican mail stops.

But we had already agreed among ourselves that we couldn’t simply gather in a park on the West Coast and buzz across the nation like a swarm of hungry locusts. The event could harm rather than help bicycle touring if we handled it wrongly. Bikecentennial needed to be organized. Many riders might be beginners, untrained and unconditioned, and to simply drift across the country without guidance could be disastrous, let alone not much fun. The goal, after all, was to hook the media and the public on bicycle touring.

So that Dan could get started on a Mexico article for National Geographic, he, Lys, and Greg flew back to Washington, DC, on July 31 to sort slides, consult with National Geographic staff, and take a one- month break. By then, even more letters had poured in about what Bikecentennial should and shouldn’t be. Very few negative reactions had been voiced:

“A traveling TOSRV, as you describe, would really publicize bicycling & I think would work.” (Don Gest: bicycle tourist, geodesic dome enthusiast, Bloomington, Indiana)

“I agree that your Bikecentennial should promote bicycling in this country.” (Milton Morse: Hemistour’s first major sponsor, Fort Lee, New Jersey)

“Can we help? List it in [our] next brochure? Give me some copy!” (Jack Stephenson: Stephenson’s Warmlite, Woodland Hills, California)

“The trouble with you (Dan) and Siple is that you don’t know when something is impossible ... and so you go and succeed. It’s amazing.” (Ralph Rosenfield: Columbus Council of the American Youth Hostels [AYH], Columbus, Ohio)

“... a rolling Woodstock that will be a permanent destructive black mark on bicycling. My only hope is that you will fail before it gets started ... ” (A.L. “Tony” Prances: member, National AYH Board of Directors, 1972-1973, Lima, Ohio)

Leaving the group in early July in Salina Cruz, Mexico, where we had stored our bikes, I bused south to Antigua, Guatemala. I had one month to study Spanish at the Proyecto Linguistico Francisco Marroquín school. But by the time the trio finally flew back to the U.S. at the end of July, I was already halfway through my studies, and we had no agreed-upon date to resume Hemistour. Although my school expenses were paid, I had little spending money and no money to travel back to Salina Cruz. Toward the end of my studies, I had neither a date to reconvene nor money to get there, and according to Greg’s letters, our National Geographic relationship seemed to be in peril. Then, in one day, I received three letters saying that Dan was ill. Out of the loop, stuck in Antigua, and alarmed, I phoned Greg at his parents’ house in Schenectady, New York.

Back in the U.S., Dan, Lys, and Greg had plowed headlong into more Bikecentennial promotion and ongoing Hemistour chores. During several days of sorting slides and meeting with National Geographic staff concerning the Mexico article, the trio made the fortunate acquaintance of Carolyn Bennett Patterson, one of seven assistant editors. As president of “Open House U.S.A.” (Bicentennial program sponsored by the Wally Byam Foundation), she presented Bikecentennial with its first major grant — $1,000 with no strings attached. “It’s awesome, that’s just the way I feel about it,” Patterson said. Such immediate financial support was both thrilling and promising.

Dan had left for Columbus, Ohio, and Lys had returned to Missoula, Montana, temporarily. But Greg had no more news about Dan’s condition except that Dan had caught a cold he couldn’t shake and was inexplicably losing weight. Our October 1 Hemistour departure date, already reset once, was up in the air again.

Realizing I would definitely be in Antigua for another month with no funds, I begged the Proyecto to give me free classes in exchange for running staff errands and working in the office. Toward the end of August, I had a letter stating that Dan had been hospitalized for two weeks to diagnose and treat an intensifying illness. He couldn’t even sit up to finish the Mexico article (never published) and was weak, his energy at low ebb, and his eyes increasingly yellow. Hepatitis had struck, and at least three to six months of recuperation would be necessary. Hemistour was in limbo.

But my parents soon wrote to offer me a flight back to the States from Mexico City, and a $300 check had at last arrived from Dan, who had received a $2,500 advance on the Mexico article. I took a bus out of Guatemala on September 6.

Back in Salina Cruz I broke down and boxed up the Burdens’ bikes and gear, hauled them under the bus with me to Mexico City, and flew them to Houston. National Geographic had stopped paying our travel expenses after flying the trio home from Washington, DC. After a staff discussion there about finances, Greg wrote, “Dan had the feeling the last time he was in Herb’s office that they were saying hello and this time they were saying goodbye.”

A Difficult Choice

Greg flew down to meet me in Houston where we had tentatively decided to get jobs to save money to try to get Hemistour back on the road as we had no money to continue. In a quandary, we realized we had to choose, and choose immediately, between Bikecentennial and Hemistour. Both needed devotion, energy, and money to keep the wheels rolling. But we had promised ourselves and fellow bicyclists in America to complete Hemistour, and it would have been unwise to wait for Dan to get well because of seasonal weather changes along the route, especially in South America. Dan’s own physician had doubts about any return to Latin America where the risk of reinfection was high and could prove fatal.

Then Lys made it perfectly clear that Bikecentennial would go forward and that she would make it happen. She started working a high-paying job at the Anheuser-Busch brewery near Worthington, Ohio. While helping to pay Dan’s medical bills, she was also saving money for Bikecentennial trail research. By October, she was in Williamsburg, Virginia, about to start the cross-country drive across what would become the TransAmerica Bicycle Trail.

Greg and I felt released — free to return to Mexico without worrying about Bikecentennial’s viability. Even though Dan was weak, he continued to churn out letters and would steadily improve.

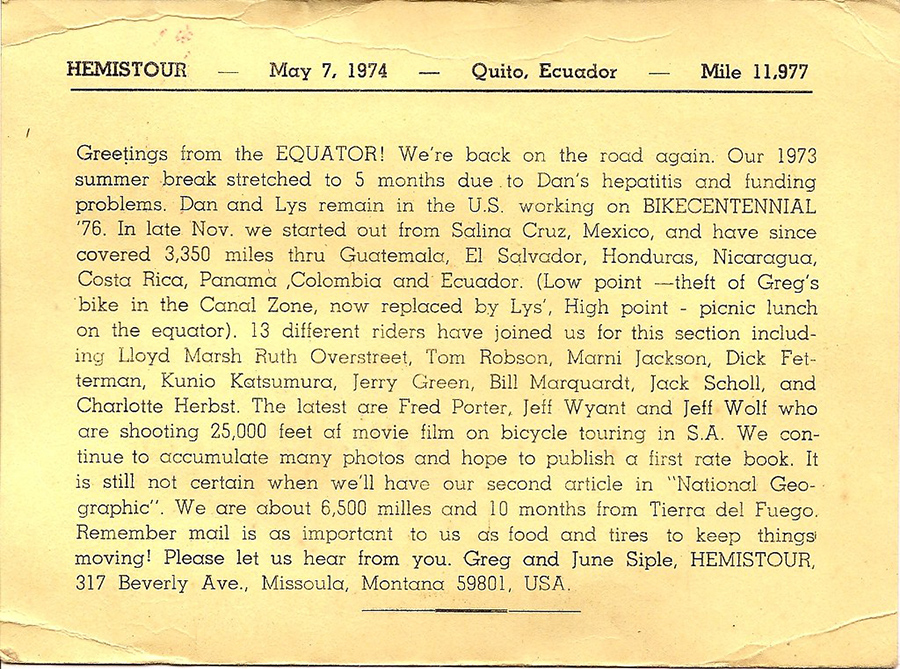

Turning down the promise of a sumptuous Thanksgiving dinner at my parents’ house, Greg and I opted instead to get back in the saddle. Back in Salina Cruz, where the Hemistour miles had ended in July at 8,628 for Dan and Lys, we finished cleaning our stored equipment and bikes — moldy saddles and all — and headed for Central America with Lloyd Marsh and his sister, Ruth Overstreet. Tom Robson had also returned, bringing friend Marni Jackson along for the ride. Hemistour was back.

We often wondered how the Burdens could have given up their Hemistour adventure, but they were pursuing a new adventure just as exciting — building Bikecentennial. I pictured Dan at his typewriter, rolling along a trail of paper instead of the open road, setting up the Bikecentennial adventure for thousands of new cyclists to come, and Lys driving along the backroads of America, laying out the route for those same adventurers. They sacrificed much to get Bikecentennial going.

April 3 is often celebrated at the Adventure Cycling headquarters as “Chocolate Day,” a sort of founder’s day staff feast of chocolate-laden potluck goodies — treats originally designated for Aztec royalty only. But I still wonder — would Bikecentennial have happened if a serious case of hepatitis hadn’t come along?

Comments

Forgot Password?

Enter your email address and we'll send you an email that will allow you to reset it. If you no longer have access to the email address call our memberships department at (800) 755-2453 or email us at memberships@adventurecycling.org.

Not Registered? Create Account Now.